Works by Flannery O’Connor are not difficult to read in the way that works by Russian authors or Henry James are difficult to read. They are difficult to read in that O’Connor held that because midcentury men and women had seen incredible things, they were harder to impress and wake up out of the doldrums of modern life. How do you stir someone who seems to be asleep?

The same question could be applied to our technologically savvy, smart phone-using world. We are so sated with entertainment that it can be mind-numbing. The whirring of gadgets no longer registers as noise to us. To arrest our attention, screenwriters and directors aim faster, harder and louder to keep us engaged. Headlines are more salacious, brazen or teasing. Considering this approach, little has changed in the 60 years since O’Connor wrote for her audience.

What does Flannery get right?

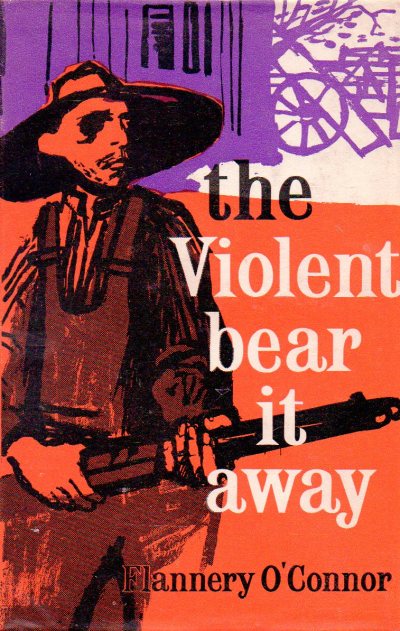

O’Connor’s work is shocking and violent. I read her second novel, The Violent Bear It Away, with relish after the dissatisfaction I felt with “Madame Bovary.”

In Madame Bovary, the novel fails because of the author’s inability to grasp and the possibility of change in the main characters. They are what they are and what they are will damn them.

The Violent Bear It Away deals very directly with our ability to make a choice, to pursue or run away from a transcendent call.

If you, like Flaubert, author of Madame Bovary, believe that man is the only measure of himself, the only one who can call himself to anything, you will disagree with this assessment. But I think there is something beyond us, something bigger than ourselves working in and out of this world.

Transcendence

A belief or experience of transcendence is such a ubiquitous concept across time and cultures that psychologist Dr. Martin Seligman listed it in his list of Character Strengths and Virtues, a concept of positive psychology that examines not what makes a man ill, but well, happy, fulfilled and flourishing.

Internal Locus of Control

Psychology also proposes that successful and well-adapted individuals likely have an internal locus of control (among other things). It is a sense that in a given situation, we can make a choice and our choices matter. Our choices affects the outcomes.

O’Connor’s vision aligns with these concepts. In all her works, we meet broken characters. Most are generally broken by pride. Pride that they are superior in their righteousness, in their class, in their skin color, in their education. It is often the humbler character of her writing who can see the bigger picture, for pride blots out a multitude of good sense.

As these characters, limited by their background or the smallness of the world, interact with the more worldly ones puffed up by pride, something happens. There is an action, an encounter, to deflate the proud. In her short stories, the action is presented in a tightly woven series of events and comes to a quick and intense ending, often deadly.

Even modern man with his gadgets and medicine cannot escape this last end.

We saw our society shaken down with fear of death as the novel virus with unknown origin, risk factors and spread came onto the stage. Anxiety persists even up to now. It has rocked those who felt safe and secure in their modern world to their core.

This, O’Connor believes, is the moment of grace. It is the moment of invitation. It is the moment to ask ourselves, when faced with the universal reality of death, “So what?”

So what? What difference will it make?

Did this last year change you?

What did you do with the anxiety surrounding death?

Those with the stomach for it, who can overcome the shocking quality of her work, find themselves returning to her work again and again. With the shock worn down by repeat exposure, they find themselves drawn into the mystery of these questions. What is the moment of grace? What is the call to transcendence? What choice does the character make? His or her actions have consequences; they mean something; they matter.

And so do yours.